How to unburden yourself: a guide to escaping overstimulation

Part three of 'The fight for our aliveness: reality vs the digisphere'

‘I dream of a quiet man

who explains nothing and defends

nothing, but only knows

where the rarest wildflowers

are blooming, and who goes,

and finds that he is smiling

not by his own will.’

—Wendell Berry, ‘Sabbaths 1999, II’

Prelude: force-fed

‘The price of anything is the amount of life you exchange for it.’

—Henry David Thoreau, Walden

You open your eyes and feel the pull. Even through the fog of your weariness it is clarion. Giving in to it is easy—all you have to do is reach out your hand and fumble for a few seconds until you’re in its grip.

You know you shouldn’t. Some part of you knows. Some part of you used to know. It doesn’t matter, your face is now aglow. Messages, email, social media, news. Outside, the blackbirds might be singing invocations of dawn. They might be. Slowly, barely perceivably, the anxiety begins to pool behind your eyes, before spilling over and trickling down into your chest.

How long do you lay there for? Before you’ve even raised your head from the pillow, more information than most people throughout history will have received in several days has been pressed into your eyes like a pair of angry thumbs.

Eventually you’re up and moving half-willingly through the day. You’re tired. It was the last thing you saw last night; it kept you, as usual, from getting enough sleep. You will keep checking it, regularly, unconsciously, spending more time staring at it than into people’s eyes. You touch it more than any lover. It has become your closest, most intimate relationship.

It keeps force-feeding you information that you don’t really need, but for some reason you let it. Pictures from a half-friend’s holiday. An advert for shoes. A blood-stained child crying among the rubble. A half-inspirational quote about self-care. News about how a politician has lied again. An advert for bed linen. A video of a wildfire consuming someone’s home, or a bomb exploding, or a cute cat playing with a baby. The distinction between these things becomes more and more blurred. It’s all content, all coming at you from the same device, the same platforms, all within seconds of the other.

Before you’ve even raised your head from the pillow, more information than most people throughout history will have received in several days has been pressed into your eyes like a pair of angry thumbs.

The average person spends about four hours doing this each day—about two months of their year, every year. You’re a little more anxious than you used to be. A little more irritable. You’re not always sure that the world is a good place. What’s more, this is all time that might otherwise be used in pursuits that keep anxiety and loneliness at bay; like developing relationships, engaging in something sensual and pleasurable, flowing out of ourselves instead of collapsing inward under the sheer weight of what gets piled upon us through our screens. Phones both increase our anxiety and take away those things that give us resilience to it.

There is a reason why I began this series with Etty Hillesum’s quote about how easily we come to accept monstrosities. We are more than fifteen years on from the advent of the social media / smartphone age, and slowly it has been normalised, woven into the fabric of our daily life. All without our consent, but yet with a numbed acceptance. It is shifting baseline syndrome in action: seismic changes that become the status quo by dint of them happening over an extended period of time. We are the frogs who before they even realise it are being cooked as the temperature slowly increases.

Intro: airstrikes

‘Beware the barrenness of a busy life.’

—Socrates

Our brains are drowning, dragged down by the disconnect between their paleolithic biology and the digisphere that now governs them. We are disastrously overstimulated—swamped by endless notifications, infinite scroll, and the pressure to be always ‘on’.

Chronic overstimulation increases stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, keeping us in a constant state of fight-or-flight, increasing anxiety. It fractures our attention, making deep thinking and sustained focus more and more difficult. Our ability to be fully present with loved ones diminishes as our gaze is repeatedly sucked into our screens. Conversations become shallower, eye contact less frequent, and our connections more fragile, as real-world intimacy is usurped by digital distractions.

Repeated context-switching—moving quickly between email, social media, work, TV, and whatever is going on around you—creates a cognitive overload that decimates our ability to process information meaningfully. Our creativity is being weakened, our capacity for self-reflection eroded, and we are left craving constant stimulation just to feel engaged.

Meanwhile, sleep—one of our main bulwarks against physical and mental decline—is collapsing; blue light from screens disrupts melatonin production, while digital hyper-engagement keeps our minds restless.

It is not a nice feeling, being convicted of so much woe. I recognise Abraham Joshua Heschel’s words about how the prophetic can be ‘embarrassing’. ‘People need exhortations to courage, endurance, confidence,’ he says, ‘but Jeremiah proclaims “You are about to die if you do not have a change of heart.”’ I sometimes feel like this: a doom-monger. But as far as technological prophesying goes, I’m on the mild side. People who know far more than you and I are sounding far starker warnings. In an article for Time magazine (hardly a hysteria rag), a leading AI researcher said that we need to be prepared to launch airstrikes against AI datacenters, such is the risk they could pose.

Starting a panic isn’t helpful. Nor is trapping people in guilt. Yet it’s also important to be able to call a spade a spade—to draw a red line around our aliveness. And we must not be afraid to stand up for what is good and right in a world that, let’s face it, seems to be increasingly led (both in technology and politics) by those without even a hint of moral backbone. Alarmism is hardly an offence when the horizon is aglow with fire:

‘If the watchman sees the sword coming and does not blow the trumpet to warn the people, and the sword comes and takes someone’s life… I will hold the watchman accountable for their blood.’

—Ezekiel 33:6

What about moderation? What about just trying to find a good balance? The trouble with that is that, because of the phycological vulnerabilities that these technologies are exploiting, we can’t moderate our own behaviour with them. If it’s your willpower versus billions of dollars of research on how to take and keep your attention, the billions of dollars of research wins. When you’re online, you’re not in control.

Do I really want to spend two months of every year staring at my phone? Do I want to spend my days tired and irritable because of a tidal wave of overstimulation? Those days that are in fact my life, the only life I will ever have, the life that could end, easily, at any moment?

‘You have two lives,’ the old proverb goes, ‘and the second begins when you realise that you only have one.’

We only have one. And we don’t have to live it like this.

Three ways to unburden yourself in the digital age

One: slow down

‘Fast and Slow do more than just describe a rate of change. They are shorthand for ways of being, or philosophies of life. Fast is busy, controlling, aggressive, hurried, analytical, stressed, superficial, impatient, active, quantity-over-quality. Slow is the opposite: calm, careful, receptive, still, intuitive, unhurried, patient, reflective, quality-over-quantity. It is about making real and meaningful connections - with people, culture, work, food, everything.’

―Carl Honoré, In Praise of Slow

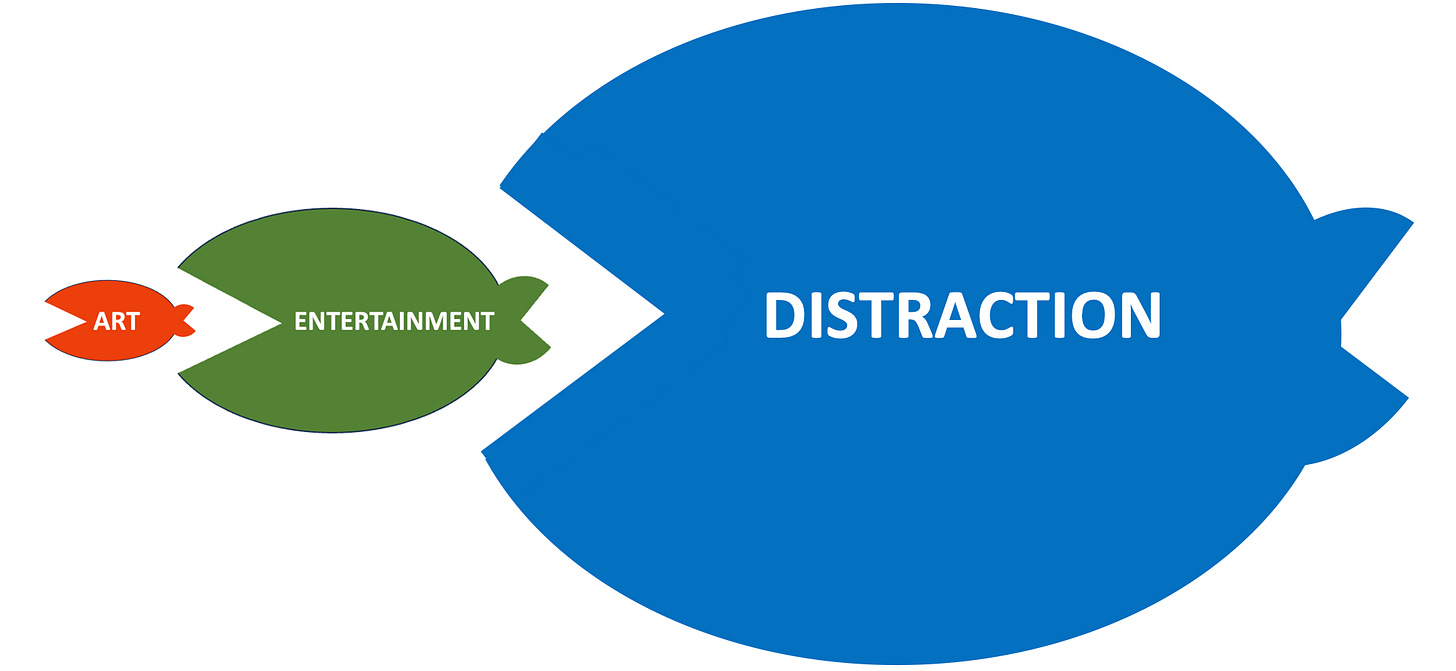

Instagram has changed the shape of poetry. And not just figuratively. It has literally altered its form. This is because the medium of poetry is more or less diametrically opposed to that of social media, and has therefore, over time, contorted itself to adapt to this new mode of communication.

Here’s what I mean:

Both reading and writing poetry requires a certain quality of attention. Poetry, and indeed all art, is the language of the soul. It reaches into, and conveys the response of, our hallowed interiors. It should be read slowly, perhaps repeatedly. It ought to be lingered over; dwelt upon; savoured.

The average Instagram post is viewed for three seconds. It’s similar with Facebook and TikTok. A good poem will seep into your bones; a social media post barely makes it past your cornea. You scroll and move on, scroll and move on, scroll and move on. It is the opposite of mindfulness.

To create a ‘successful’ social media post—one that gets high ‘engagement’—you need something that provokes a more or less instant reaction. ‘Instapoetry’ thus becomes more aphorism than poem, stripped of the ambiguity and nuance that makes poetry, poetry. It tends towards the trite; something that can provoke a quick but not lingering reaction. In poetry, the unsaid is just as important as the said, but the Instapoem just blurts it all out.

A good poem will seep into your bones; a social media post barely makes it past your cornea.

I’m wary of coming across snobbish here. There’s nothing wrong with writing things like that. Doing it well can be an artform in and of itself. The trouble is that it has become reflective of our wider lives. Art imitates life, and speed, consumption and distraction has become the essence. The message inherent in the smartphone is: faster is better.

I want to live my life like a poem, not an Instagram post. I want to experience it, not consume it. I want to move through it slowly, not scroll through it in search for the next quick hit.

Thoroughly buttered

‘What is all this juice and all this joy?’

—Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘Spring’

Slowness shouldn’t be a hard sell, because at its core is sensuality: the bliss of embodiment. ‘The central tenet of the Slow philosophy is taking the time to do things properly, and thereby enjoy them more,’ says Carl Honoré is his book on the subject. When we hurry, we skim the surface of our lives. Gratification that is instant is not really gratifying. I want depth.

You can easily and freely increase your enjoyment of life, and the everyday activities within it, simply by slowing down, by being present to what you’re doing (remembering that to pick up a phone is to evacuate the present). Two obvious examples are food and sex. You can gratify yourself in a quick and perfunctory way, or you could take your delicious time, and be truly, profoundly, gasp-inducingly satisfied at your deepest human level. I’m talking about preparing and eating a good meal, obviously.

De-accelerate your life. Make a habit of doing the slow thing, of lingering. Where is it that you’re in such a rush to get to, anyway? Life happens here, not there. Speeding up, therefore, is a waste of time. Life doesn’t happen upon arrival; it happens while you’re on the way. So meander. Obambulate (one of my favourite words; it means to wander about in a kind of pleasurable aimlessness). Be mindful, present, attentive. Do not seize the day, but luxuriate in it; let it slowly unfold.

Where is it that you’re in such a rush to get to, anyway? Life happens here, not there.

Two: cultivate silence and solitude

'The quiet mind is richer than a crown.'

—Robert Greene, 'Sweet are the thoughts'

You wouldn’t have thought that a bit of peace and quiet would freak people out, but that’s what it did.

A few years ago, an organisation that I worked for introduced ‘Sabbath days’. These were working days where the instruction was to not work. The time was instead to be given over to quiet reflection. Reading, writing, thinking, prayer. And it drove some people crazy. They wondered around the building in a twitching daze, not knowing what to do with themselves.

When you are accustomed to constant stimulation, silence can be terrifying. A mind that isn’t quiet will at first find quietness intolerable; yet the more time we spend in it, the more it will seep into us. Of course, we must make some room for our neurodiversity here: we’re all wired a little differently, and will have different levels of tolerance when it comes to stimulation. But the heart of the principle remains the same.

I once went on a silent retreat and spent much of the time weeping. There was something going on in my life that I hadn’t confronted (far easier to numb or distract myself away from it), but once that vacuum of silence had been created, it was filled with a pain that I had to wrestle with. It was hard, and I needed the guidance of a spiritual director, but I was better off for it. Whatever secrets our souls are holding on to, be they soft or sharp, we won’t be able to learn them if we never stop to listen.

The bigger yes

Solitude is not about isolation. You don’t need to hide in a cave. Solitude is simply creating space in which you can be present, free from interruption. It is about giving your mind and soul the opportunity to stretch their legs.

But in the digisphere, solitude is dead. We can’t even wait in line without whipping out a phone, let alone spend hours lost in reverie.

We need to recover the art of being alone, to reinhabit those moments that were once unstructured and unmediated: time spent staring out of a window, daydreaming, or simply existing without the pressure to ‘do’ something. It is in stillness that we arrive at the truth of ourselves; it is in quietness that we begin to gain the trust of our shy depths.

What has no boundaries has no shape, and our devices have become so infused into our lives as to make us amorphous. In the digisphere we are always on, always available, always answering to incessant demand. This expectation is new in human history, and it is not one we have to accept. Saying no to the digisphere is not an act of rejection, but one of prioritisation. It is the no that is in service of the bigger yes. The world will not fall apart if you step away, but you might fall apart if you don’t.

What has no boundaries has no shape.

Retreat to re-engage

‘We are drowning in information while starving for wisdom.’

—Edward Wilson

The fear of missing out keeps us tethered to technologies that deplete us—ironically making us actually miss out on the things that really matter. Retreating from the digisphere doesn’t mean disengaging from the world; rather, it gives us the space to engage with it in a far deeper and more meaningful way.

Echo-chambers, the proliferation of misinformation, and the instantaneous nature of online discourse mean that social media is pretty much the worst possible way to stay ‘up-to-date’. The digisphere rewards the immediate reaction over the thoughtful response, the hot take over the nuanced discussion. Therefore to be hyper-informed is, in many ways, to be ill-informed.

True understanding requires distance, reflection, careful consideration, and also engagement with people outside of your sphere. Instead of consuming a never-ending stream of updates, choose depth: read a well-researched article in a physical newspaper, listen to a long-form discussion, subscribe to an analogue weekly digest from a reputed source. Keep informed, but in a gentler, more mindful way. Stay away from the ‘feed’: it’s probably feeding you nonsense.

To be hyper-informed is, in many ways, to be ill-informed.

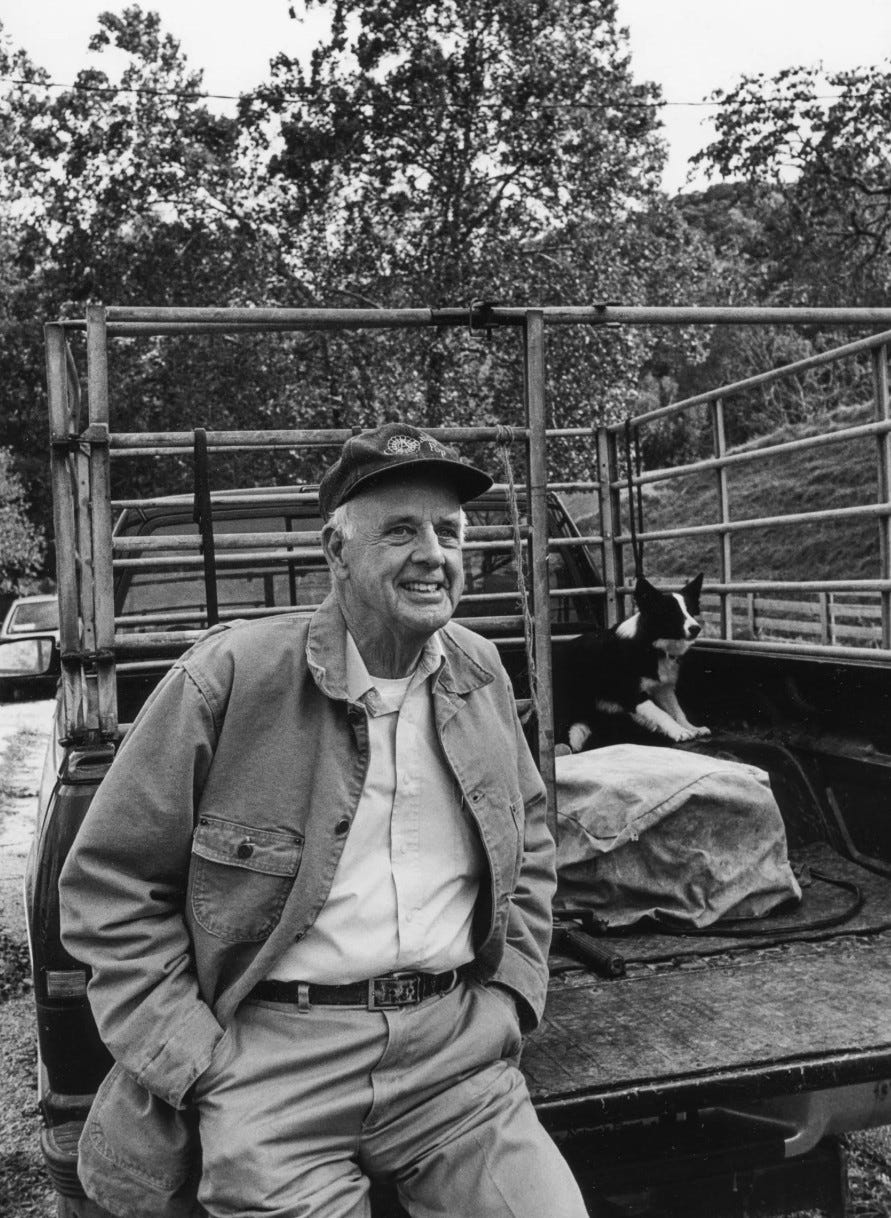

It is also a fallacy that online presence is necessary for meaningful action—that to make a difference, we must be visible, vocal, constantly engaged. Many of the most profound thinkers and change-makers of modern times lived lives of deliberate solitude. Abraham Joshua Heschel, Thich Nhat Hanh, Thomas Merton, Wendell Berry—all activists who have had a profound influence, but are as far away from an ‘influencer’ as you could imagine. They shaped the world, not through ceaseless digital engagement, but through contemplation, and through words and actions that carried real weight. Berry still, in 2025, refuses to own a computer, let alone a smartphone. Mandela, Gandhi, Dr King… maybe they would have had an online presence had they lived in a different time, but the fact is they changed the world far more than you or I ever will, and they didn’t need the internet to do it.

It’s extraordinary that we’ve been convinced that these technologies are necessary when they’ve hardly been around for any time at all.

A similar principle applies to our relationships. If abandoning social media causes a friendship to fade, was it really a friendship? We’ve connected for millennia without curated feeds and algorithmic nudges, and probably done a better job of it. True connection is not a like or a comment on a post; it is a conversation, a letter, a shared moment.

Weave solitude into your daily life. Be less available. Make space for the quiet, for the slow, for the unstructured. You’ll feel better, be better informed, and be better connected in the long run. Unplugging is not a withdrawal, it is a return, a teshuvah—to the depths of life.

Three: remember how to rest

‘Drop thy still dews of quietness,

till all our strivings cease;

take from our souls the strain and stress,

and let our ordered lives confess

the beauty of thy peace.’

—From the hymn ‘Dear Lord and Father of Mankind’

Warm, bright sunlight. A cold, sweet drink in your hand, beads of condensation dripping down the glass. The rhythmic crash of waves. The giggling of children. A breeze bringing you coolness and freshness and salt. You lay back, the definition of relaxed. Then you feel the familiar tug. You’d better take a picture of how much you’re relaxing. Then you can post it and tell everyone else how much you’re relaxing. While you’re there, you might as well scroll for a while to check if anyone else is relaxing as much as you are. ‘Quick, kids, stop playing! I need to take a picture to show people how much you’re enjoying yourselves!’

I think there’s one thing we can confidently say that you’re not doing here, and that’s relaxing.

Smartphones are anathema to true restfulness, because rest requires presence. The best holidays I’ve had either took place in the pre-smartphone era, or have been ones where, immediately upon arrival, my phone has gone into the hotel safe and not come out again until it’s time to leave. There was even the one a couple of years ago where I lost my phone part-way through, and ended up having more of an adventure as a result.

Secret valleys

Be honest with yourself: when was the last time you felt truly rested? Refreshed, restored, rejuvenated? More awake, more aware, more alive?

How regularly do you feel this way?

Conversely, when was the last time you felt weary? When was the last time you felt frazzled, stretched, anxious, overwhelmed?

How regularly do you feel that way?

I thought so.

We might have forgotten how to rest. Or, perhaps more accurately, the digital landscape we now live in makes it more or less impossible to rest.

Rest is sensuous, embodied, simple, pleasurable, present, nourishing, human. Rest is watching a good film, reading a book, going for a walk in the woods, luxuriating in a bath, listening to music, sitting drinking a cup of tea while listening to the rain. None of these things are improved by the presence of your phone; quite the opposite. Phones are presence killers, and thus barriers to real rest.

Phones are presence killers, and thus barriers to real rest.

I love this description of Rivendell, one of the homes of the Elves in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings:

‘Elrond's house was perfect, whether you liked food or sleep or story-telling or singing (or reading), or just sitting and thinking best, or a pleasant mixture of them all. Merely to be there was a cure for weariness. ... Evil things did not come into the secret valley of Rivendell.’

—The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Tolkien listed the available activities at Rivendell like this for a reason. Each feeds a different part of our being: Body (food and sleep), soul (story-telling and singing) and mind (sitting and thinking). Perhaps the special healing power held in Rivendell isn't special at all, it's simply that it's a place that makes it easy to do the things we ought to be doing in order to rest.

The things that heal us of our weariness are not complicated or expensive. They are, however, increasingly marginalised by the digisphere. In our culture, sleep is seen as a luxury, rather than a necessity; food is made to be convenient, rather than nourishing; connection has been outsourced to screens; and busyness and distraction have all but eliminated the ability to reflect.

We need to remember how to rest—to create secret valleys of healing in our lives.

One way we can do this is by reviving the Sabbath. I like Heschel’s description of the Sabbath as ‘the day on which we learn the art of surpassing civilisation.’ Walter Brueggemann similarly defines it as a ‘withdrawal from the anxiety system of Pharaoh, the refusal to let one's life be defined by production and consumption.’ There should be one day each week when we are non-negotiably unplugged.

Sabbath is a day for soulfulness, for allowing our being to breathe. Sabbath declares that rest is not a luxury, but part of the fabric of our living. It is a sanctuary in time; a safe harbour no matter what storms the week may bring. Fill one day each week with whatever it is that delights you; find the wonder, the beauty, the peace. It’ll be there if you look for it—if you intentionally create space for it. But it won’t happen by accident.

Without the grammar of rest, our lives are but a stream of consciousness. With rest—intentional, present, regular rest—they become poetry.

Coda: dawnbirds

‘Spirituality has much more to do with subtraction than it does with addition.’

—Richard Rohr, The Art of Letting Go

And what is it that I want to achieve?

To write, with pencil or pen, each moment

so slowly—each letter, each word so lucid

with feeling—that life cannot help

but be a poem.

To know, simply in my nature,

where I might find a particular star

on a particular night; the phase of the moon;

what the roots make of it.

To make learnings of stillness, quiet;

to take their lessons to heart and to pray

so unobtrusively, so entirely present,

that the dawnbirds come to feed out of my hand.

©Gideon Heugh, Naming God

A little note to say…

I won’t be putting The Green Chapel behind a paywall. I believe that poetry and ideas about God and other beautiful things should be as accessible to as many people as possible. Having said that, I am an independent artist, so I need all the support I can get! If you’re able to make a small contribution to my work, I’d be incredibly grateful. It will help me to keep doing what I’m doing, and keep it free. Just click the button below. Thank you, GH.

Today I took a picture of a deer who came and stood right in front of me on my porch (to "share" it) and then felt such grief. I could almost see my reflection in her big dark eyes, with that device between us. What an atrocity. I thought of you, taking pictures of the stars with your daughter. It's agonizing, being addicted to a computer. But we are not powerless. I deleted Facebook last week, and after reading this Instagram has now gone. Both acts felt like a sigh, like taking off my shoes and walking on wet earth. Thank you, truly.

Please keep writing about this. Each time you do, I delete my social media apps…again. In time, they will lose the fight to return.